Interview Series: “Media Memories: Media Archaeologies and Digital Society” Universal and Local Faces of Media Archaeology

Dear Professor Huhtamo, you are widely recognised as one of the pioneering figures in the field of media archaeology. In your view, what is media archaeology? When writing Illusions in Motion, were you intellectually influenced by Ceram’s book Archaeology of the Cinema?

I have often said that there are media archaeologies rather than a single media archaeology, because there are significant differences between the ideas of its practitioners like Siegfried Zielinski, Wolfgang Ernst, and myself. I try to clarify these differences in my forthcoming book Fairy Engine: Media Archaeology as Topos Study (The MIT Press, 2026), which is an extensive presentation, both theoretical and practical, of my version of media archaeology. I call it “media archaeology as topos study” or “topos archaeology.”

I read Ceram’s book early on, in my 20s, and it certainly inspired me, especially the illustrations that depict objects from John and William Barnes’s pioneering collection in England. I was less inspired by the text, which I found narrow-minded and linear, very conservative in its teleological emphasis. Ceram discussed moving image technologies as anticipations of cinema, which he presented as a kind of culmination. I could not agree with that. I saw media archaeology as something layered and multidimensional, more like a vast field in slow transformation than a group of vectors pointing to the same direction. For me, cinema was only one of the many manifestations of the moving image culture. One of the reasons for my reaction was my interest in interactive media and virtual reality, which were also influenced by 19th-century devices like phenakistiscopes, zoetropes and stereoscopes. Those devices were part of a dynamic field of many possibilities. Interconnections, also lateral and diagonal, in general: spatial, were more important than chains of influence. Both material and discursive things matter to me; that infleunce each other.

For me media archaeology is a critical approach rather than a “media science.” It is a way of making sense of media culture by putting past(s) and present(s) into dialogues between each other. The past(s) help to clarify the present(s) and vice versa. The scholar server as an instigator and moderator and to an extent as an interpreter. It is important to draw a line between what I call “the inscribed” and “the projected.” There are things that are inscribed into objects and discourses preserved from the past. They refer to things that really happened. “The projected” refers to the “distant observer’s” (the researcher’s) interpretations superimposed on the past. Both aspect are always required, but it is important to be alert about their relationship. It is too easy to confuse “the projected” with “the inscribed” and vice versa. Media archaeology should be based on excavations of actual historical remains. “Excavation” should be more than just a metaphor. It refers to actual archival work (as Walter Benjamin did while preparing The Arcade Project, an anticipation of media archaeology) and also to field work, where it can resemble aspects of industrial archaeology, for example.

In works such as Mareorama Resurrected, you combine media archaeology with the performing arts. What kind of impression were you hoping to create in the audience regarding media archaeology through this approach? And what has been the most interesting feedback you’ve received about this field so far?

Mareorama Resurrected was a performance art project that developed as a side project from the years-long research I did for my book Illusions in Motion (2013). Although writing is my primary means of expression, I have a long history of working together with media artists as an exhibition curator and sometimes as a collaborator (I created and performed another stage performance, Musings on Hands, with Golan Levin and Zachary Liebermann at Ars Electronica, Linz, for example). I am also an experienced lecturer. Therefore I am interested in experimenting with different modes of expression, including installation works (I have done some). They are another way of creating dialogues and stimulating the minds of the audience. I wants to open the eyes and the ears – performance, like theatre, helps!

Mareorama Resurrected was a kind of one-man play where I took the audience to the 1900 Universal Exposition in Paris to experience Mareorama, a lost moving panorama spectacle. It was part lecture, part play, part reconstruction of the past. I hope the audience understood it was not the same thing as Illusions in Motion. There was a creative dynamic between them which was deliberate. I have done similar things by creating magic lantern shows, performing with musicians and sound effect artists. These performances are media archaeological meta-art, commenting on the past, but really moving between different moments in time and impersonating identities in flux; partly about what really happened, partly fiction.

It is a great honour to interview someone like you, a pioneering figure in media archaeology. I have also written the first officially published thesis on media archaeology in Turkey, within the national thesis database. My approach was to combine my previous fields—Classics and Information Technologies. What are your thoughts on bringing together the old and the new in this way? What advice would you give me for establishing, developing, and promoting this discipline in the future?

I think I already answered this question, at least partly. My work covers very large areas, especially in the new book, Fairy Engine. It is very fluid and kinetic, drawing connections and especially, asking a lot of questions. For me questions are more important than answers. Without good questions culture, and research as part of it, does not develop. Media archaeology is not the same as cultural history, because it reserves itself a right to move back and forth in time and space, kind of like traveling in a Time Machine (Zielinski often uses this parallel). It can be a bit anarchistic, in a positive and constructive sense. Media archaeology also breaks down barriers from between approaches and disciplines. That is why it is always controversial and should be. In that sense scholars like Aby Warburg and Walter Benjamin are great models for it. Warburg did not like “border guards” – me neither!

You recently participated as a keynote speaker at the Festival de la Imagen. In this context, what are your thoughts on the formation of initatives like Media Art Histories or ADA, and what do you believe are the benefits of this platforms? What role do media art archiving and, in particular, archiving practices have within media archaeology?

I have been on the board of the Media Art Histories conference series from the beginning, and also contrubited to other such initiatives. I think that they are very important, because media archaeology is somewhat scattered – as I said, there are many media archaeologies, so opportunities of putting them into dialogues and connecting the practitioners are really important. The goal is not create any kind of an orthodoxy – rather, continuing and vigorous dialogues or polylogues.

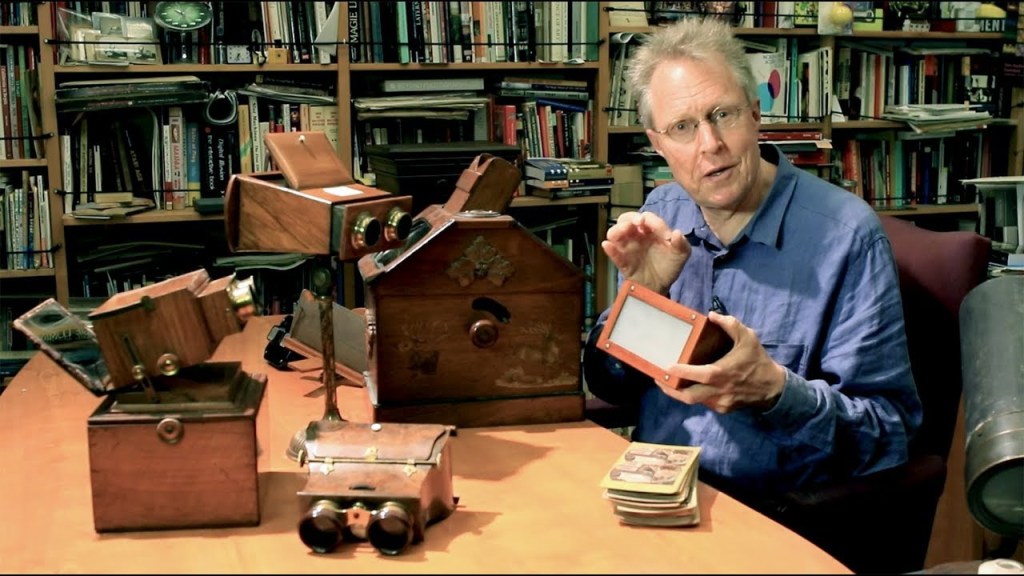

Media archaeological archives are a challenge. They are hard to put together, maintain and finance. Many institutions still don’t understand what media archaeology is and why it matters. I have been putting together my own media archaeological collection for 30 years, because I have discovered items that no one else was preserving. I had to save them. I have used many of them in my research and also helped others, for example doctoral students. My collection is large, but currently I don’t know what will happen to it when I am gone.

We have established an online platform called Archaeomedia in Istanbul, which publishes interviews on media archaeology and aims to support academics, artists, and students working in this field. In your opinion, can such platforms help raise greater awareness of media archaeology? Do you have any future projects in mind related to media archaeology?

Initiatives like Archaeomedia are extremely important, because the future prospects of media archaeology are cross-cultural and international. Media archaeology may have originated in Europe, but it has potential to be useful in many countries and cultures around the world. However, it must be adapted and localized, because all cultures are different. For that purpose, both local hubs and cross-cultural initiatives are needed. They can take many forms – online platforms, festival, conferences, magazines, collaborative projects, etc.

Personal relationships between likeminded (or different minded!) scholars will help. We need people with knowledge about their own cultures, and also with language competence. I have done much work in Japan, and written the first book on media archaeology for Japanese students and scholars, but I don’t know the language well enough to be able to research the Japanese culture from a media archaeological perspective myself. I need help from local specialists. Ultimately, the task of Japanese media archaeology is in their hands.

Within the scope of the Festival de la Imagen, I also conducted a study titled “Artificial Mind Creation,” which addresses the media archaeology of AI. There are also figures like Egor Kraft, who combine media archaeology with artificial intelligence in exhibitions. How do you envision the future relationship between artificial intelligence and the field of media archaeology?

This is both an extremely important and extremely difficult question, partly because it deals with currect developments that are very unpredictable. I recently saw a great exhibition in Paris, curated by Professor Antonio Somaini, who is a specialist of both media archaeology and artificial intelligence. It was shown at Jeu de Paume and titled Le monde selon l’IA / The World Through AI (2025). It demonstrated that AI has a history that can be excavated by media archaeology. Professor Simone Natale in Turin has done work on this as well, going back to the 19th century.

At the same time, AI will be producing material that must be submitted to media archaeological analysis. It produces texts and images that include weird versions of commonplaces and symbols from the past, but also creates ones of its own. How the creations of AI are and will be related to humankind’s inheritance is a very big question. The situation is very liquid, but I am trying to follow the developments the best I can. I personally do not use AI as a research tool, because I don’t trust enough in its creations. However, I am interested in its “hallucinations” which remind me of Surrealist automatic writing.

Yorum bırakın